These are seemingly common-sense questions. But in both cases, like many things in life, while it may seem like there's an easy, common-sense fix for it, the answer is really not so easy. This calls to mind a quote from the American essayist H. L Mencken:

"There is always a well-known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong."

In fact, the explanation is so multi-faceted that I thought it deserved its own page here instead of being buried in the FAQ or construction questions pages.

The short answer is that there usually is a lot of planning going on, and developers are typically responsible for making some road improvements. It's just that this mostly happens behind the scenes, so most people don't know it's happening and aren't aware of the realities and constraints that prevent the process from keeping up with new development. This page is an effort to give some insight into the planning process and constraints. A lot of this is from a San Antonio perspective, but it applies to most communities in Texas.

Major thoroughfare plans

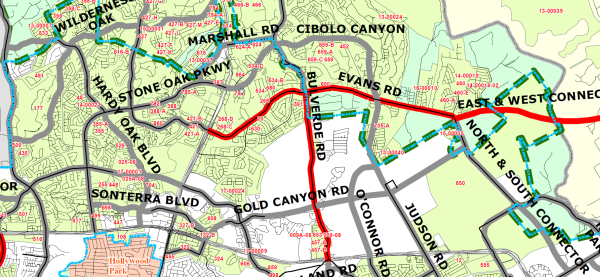

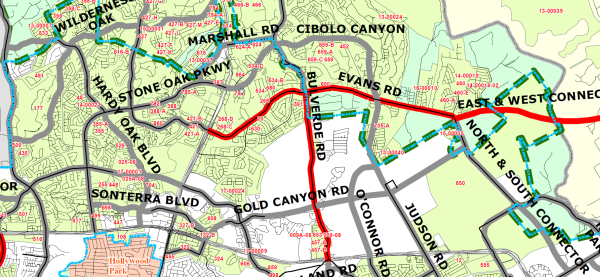

While it may not seem like it, transportation planners do plan for new development. But most of it is rather arcane and wonky, so most average folks are completely unaware of it. One example is the Major Thoroughfare Plan, which most cities and many counties have. Besides designating and classifying existing arterials, which is required for state and federal transportation funds, it also maps out the routes for future thoroughfares. When a new development is built, if it's on the route of a planned thoroughfare, the developer is usually required to donate the right-of-way and/or actually build the section of that road through their development. The plan is updated every few years.

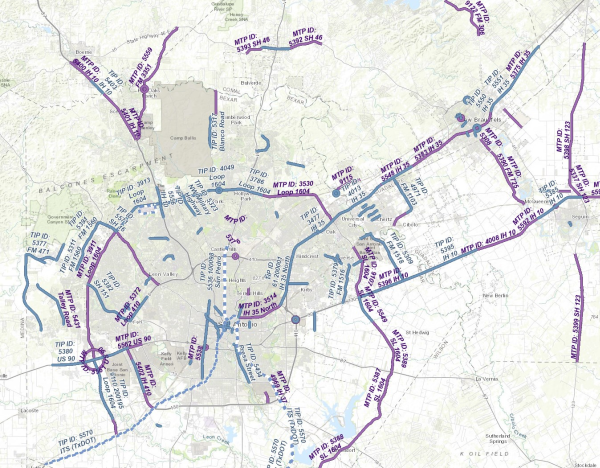

Snippet of San Antonio Major Thoroughfare Plan showing existing and planned arterials in North Central Bexar County

Comprehensive plans

Most cities also have comprehensive plans, with transportation a key component. In San Antonio, the current comprehensive plan is the "

SA Tomorrow Plan". These plans tend to be more of a high-level framework or "big vision" plan, but often drive the more nuts-and-bolts decisions made by planning agencies and policymakers. Oftentimes, there will also be subregional plans for specific neighborhoods and corridors.

Metropolitan Planning Organizations

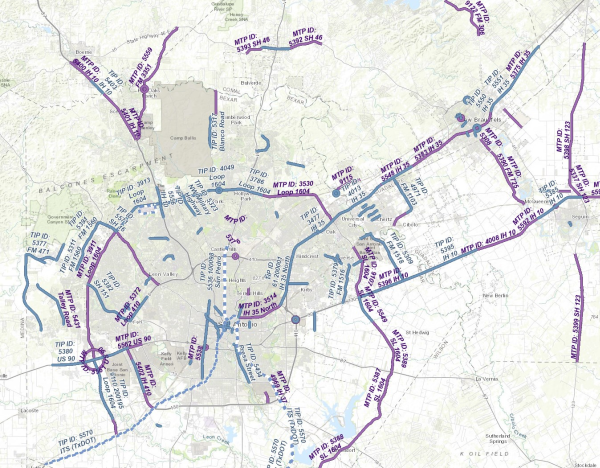

All metropolitan areas are required by federal law to have a

Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) to coordinate and plan the spending of federal and state transportation funds. (

Here is a list of the MPOs in Texas.) Each MPO has to have a short-term (4 year) and long-term (25 year) plan that is approved by a policy board comprised of local elected officials who are typically appointed to the MPO by their respective jurisdictions. Projects in the plans are submitted by the various agencies in the area, and all projects in the plans must have a designated funding allocation (i.e. money budgeted for it) — this is to ensure that the plans are realistic. Since needs and funding levels change often, the plans are updated about every two years and five years respectively. TxDOT also has it's own short-term (STIP) long-term (UTP) plans which incorporate and inform the corresponding MPO plans.

Map showing projects in 2022 Alamo Area MPO plans

"Shovel-ready" plans

TxDOT and many other agencies also have schematics developed ahead of time for major upgrades that are likely to be needed at some point. For example, in San Antonio, TxDOT has had preliminary schematics for a full freeway for SH 211 since at least 2007, even though such a project is still at least a decade away even today. Having these plans help to keep these projects as close to "shovel-ready" as possible so that, when they are needed, they can get environmental approval and funding more quickly. This can be, and has been, especially helpful when unexpected funding comes along, such as federal economic stimulus funds, air quality grants, increased state or federal infrastructure funding, or unexpected budget surpluses. The current expansion of SH 151 in San Antonio, for example, was able to be accelerated by two years because it was shovel-ready when unexpected funding became available.

Developer plan reviews

Finally, with regards to planning for specific developments, developers are required to submit plans for their developments to the city or county where it is reviewed for compliance with various laws and policies as well as esoteric technical issues. Besides the basic subdivision plat, larger developments typically have a Master Development Plan, which is an overarching conceptual plan that then guides the detailed design of the individual units within the development. The MDP lays out the land use, major roads, access and egress points, green space, and other high-level components. One required element of these MDPs, as well as many smaller standalone projects, is a Traffic Impact Analysis, which will be discussed in a bit more in the next section.

Developers do pay for road improvements

As mentioned in the previous section, when a developer submits their plans, one of the requirements in most cases is to conduct a Traffic Impact Analysis (TIA). A TIA analyzes whether the existing transportation infrastructure in the vicinity can accommodate the traffic projected to be generated by the planned development and, if not, what improvements would be required to do so. Typically, a TIA will identify the need for turn lanes, traffic signals, median openings, arterial extensions, transit amenities, and pedestrian/bicycle facilities. The developer is then required to construct any mitigation improvements identified in the TIA, or in some cases can instead pay an impact fee and/or donate right-of-way for a planned public improvement. The policies vary by jurisdiction; you can read San Antonio's TIA requirements

here. For state highways, TxDOT's process and requirements are listed

here.

Traffic Impact Analyses don't determine wide area impacts

That said, TIAs only capture impacts and require improvements in the immediate vicinity of the development. (In San Antonio, it's up to 1½ miles away.) The reason for this is that it becomes increasingly difficult to impossible to accurately gauge the impacts of a specific development the further away you go. Furthermore, the new traffic from a single development several miles away is usually just a small percentage of the traffic at a given location, so even if it can be accurately determined how much traffic from that new development will travel past that point, it usually would not be enough by itself to require mitigation based on proportionality (

see next bullet).

Proportionality considerations

Proportionality is the legal construct that holds that a developer is only responsible for mitigating their share of impact. So even in cases where it can be predicted that most of the traffic from a new neighborhood will, for example, travel down a single thoroughfare to the nearest freeway, that one development on its own is not likely to have the proportional impact that would require them to foot the bill for a major road expansion. For example, even if a study shows that traffic from a new development would likely push an existing busy road over capacity, that developer can't be made to pay for expanding the road just because they "tipped the scale"; their development is only responsible for their portion of the impact. And, even in cases where the first development in an area causes the little farm road that runs by it to exceed capacity, requiring that developer to pay the entire cost to expand the road would be unfair because other developers would then have the advantage of that expanded road without having to pay for it. Furthermore, as the area gets built out, the share of traffic on that road attributable to that first development will decrease. Moreover, people often overestimate the traffic attributable to any single development (apartment complexes seem especially prone to this). Instead, it's typically the

cumulative impact from multiple developments over time, and there is no mechanism to go back and retroactively assess specific impacts back to individual developments that were built well before contemporary traffic problems arose.

Transportation projects take time

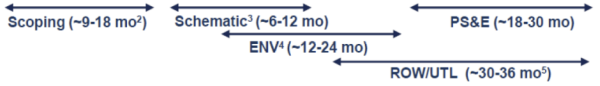

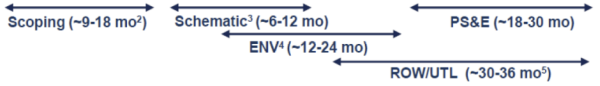

Even if planners had a crystal ball and could accurately predict developments and their impacts, it still takes several years before major road projects can come to fruition — that's just the reality of the process. There's the initial study and scoping, design and engineering, environmental studies and clearances, obtaining funding, right-of-way acquisition, and utility relocation. All of that has to happen before the actual construction to build or improve a road can start. Each of those steps can take a year or more, and even though some of the steps are overlapped (

see below), it's still generally a minimum of four years or so before a major road project can go from inception to groundbreaking in the best case scenario; six to seven years is more typical, and longer for the biggest projects. In the meantime, with few exceptions, developers can't be legally prohibited from continuing with their project so long as they have met the local and state requirements. As a result, those new developments are often well underway or even complete — and therefore adding traffic to local roadways — well before road projects can break ground. As mentioned earlier, many agencies develop basic schematics and get preliminary approvals for some foreseeable projects ahead of time to help shorten the timeline as much as possible. However, federal transportation planning rules limit the extent to which that can be done so as to focus planning resources for projects to address more demonstrable needs.

General TxDOT project development timeline

(Source: TxDOT)

Public projects can't be built without a demonstrable need

While planners do make projections and monitor traffic volumes and crash history on roads to try and anticipate where improvements will soon be needed, there generally has to be an empirically demonstrable need for a project before it can get approved and funded. And if you think about it, that's good public policy. If governments were to build or expand a road based on theorized future development that never occurred, or if an actual proposed development ended-up not being built for some reason, and as a result, the expected traffic never materialized, that would be a lot of wasted tax dollars that could have been spent on something else that was needed. Plus, there are the costs for maintenance of those resulting facilities. Given that there isn't enough funding for existing needs, spending those scarce resources on projects that can't objectively be shown to be needed really doesn't make good sense. Finally, such a policy would be ripe for abuse (i.e. "pork barrel" and "road to nowhere" projects). In short, transportation planning is a bit of a chicken-and-egg exercise, and state and federal requirements to empirically justify the need for expenditures will always result in incremental, lagging, and sometimes disjointed improvements. While not always ideal, this approach is necessary to safeguard appropriate stewardship of public funds and ensure a balanced approach to address the plethora of needs.

Developers have a head start

In order for the city/county/state to plan for infrastructure, they have to know what's coming. That happens when developers files their plats for new development. Once that happens, the clock for approval starts ticking, and as long as the developer has checked all the boxes required in state law and local subdivision regulations (which mainly deal with things like water accessibility, wastewater, drainage, road standards within the development, and a few other technical matters), then the plans have to be approved within a specified time period. At that point, most developers are fairly close to being able to finalize their plans and start turning dirt. Meanwhile, planners are just becoming aware of what's coming and being able to estimate the impact, and to start plans to address those impacts. As discussed above, the process for planning a road expansion, funding it, getting environmental approvals, acquiring any needed right-of-way, and relocating utilities takes several years. By that point, most of the early developments that prompted the expansion plans have been built-out or nearly so for a while.

Texas favors property rights

Finally, it's important to remember that Texas is a conservative state, and so the legislature and courts often favor property owners in disputes with regulatory agencies. As a result, cities and especially counties have limited authority to block development. They can regulate basic infrastructure, mainly roads within the subdivision, water, wastewater, and drainage, but those requirements must be reasonable and proportional. Developments that meet established standards cannot be blocked simply because local officials or residents feel there is too much growth occurring. Cities can enact short moratoriums on development if they can clearly demonstrate that new development would cause a critical shortage of essential public facilities. But these moratoriums can only last a few months, the city has to work diligently to address the shortage, and the moratorium can be extended only if the city is making reasonable progress to address the shortage and it sets a definite reasonable duration for the extension.

As cities in Texas are now heavily restricted from annexing, more and more development is occurring outside of city limits, either in cities' extraterritorial jurisdictions (ETJ) or beyond. Since cities' regulatory authority is substantially limited in the ETJ, and since counties have even less authority to regulate development, the ability for government to manage growth, and for citizens to have a say in development standards, will be even more limited in the future unless the laws are changed, a proposition that seems highly unlikely in the current political environment in Texas.

So I hope that helps to answer the two questions in the title of this page and reveals the immense legal and practical complexities of transportation planning. Could things be better? Sure, there's always room for improvement. But hopefully now you understand what the constraints and pitfalls are and how, while not perfect, there is a pretty solid and refined process in place to address current needs and to try to plan for future ones.

Other sites of interest